Articles

Slovacko, the Region of the Painter’s Palette (pg. 20 -21)

Link will direct you to the National Treasure: The Art of Joža Uprka from the George T. Drost Collection. Please see the above page numbers for the article.

Where so many colours in Slovácko came from, no one will ever know. Different traditional costumes, different embroidery and different head scarves distinguish every village. The palette of colours and Folklorist at the pilgrimage to St. Anthony’s chapel above Blatnice used to be unbelievably varied and it is no surprise that was where the biggest painter of Slovácko, Joža Uprka, set up his canvas to use his brush to capture all the beautiful impressions.

Joza Uprka’s Modern Traditionalism by Dr. Nicholas Sawicki (pg. 17 -19)

Link will direct you to the National Treasure: The Art of Joža Uprka from the George T. Drost Collection. Please see the above page numbers for the article.

When Uprka’s friend Mucha accompanied the Parisian French sculptor Auguste Rodin for a groundbreaking exhibition of Rodin’s work in Prague in 1902, they also traveled to Hroznová Lhota to visit Uprka at his home and studio. Uprka and Mucha arranged for Rodin to be accompanied part of the way by young men dressed in folk attire, riding on horseback in an emulation of the traditional ceremonial procession called the “Ride of the Kings,” common in Slovácko and usually held on the Pentecost. Uprka knew the tradition well, and painted at least two large, monumental oil paintings documenting the ceremony, in 1894 and 1897 respectively.

A Brief History of Joža Uprka and His Rise to Fame Dr. Petr Vašát Nadace Moravské Slovácko (Moravian Slovakia Foundation) and Founder of the Joža Uprka Gallery, Uherské Hradiště, Czech Republic (pg. 13 - 24)

Link will direct you to the National Treasure: The Art of Joža Uprka from the George T. Drost Collection. Please see the above page numbers for the article.

Over time, the Uprka gallery also became a meeting place for Moravians living in Prague. To me, it is symbolic that one of the first important foreign guests in the newly founded gallery in Prague was George Drost, an American who was born in Brno. As it turned out later, this gregarious man was a collector and also a tireless supporter of Joža Uprka›s work, especially within the United States. This is evidenced by this exhibition in Cedar Rapids, which is clearly a highlight of his longterm determination to introduce.

Our Czech Millet: Joza Uprka Between the Traditional and the Modern, by Dr. Marta Filipová

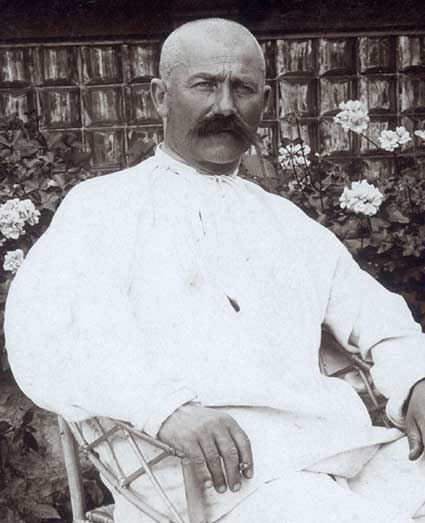

His work (fig.) in many ways symbolizes the transformation Czech society and culture underwent around the turn of the century. Increasingly secularized, the urban middle classes started to relate to French and occasionally German paradigms rather than looking inwards. Traditions and customs, as well as folk arts and crafts skills, were disappearing from villages while the modern lifestyle of the cities required modern artistic language. Uprka (fig.) represented an attempt to capture the disappearing colourful, almost bucolic world of the village in the face of fast‐changing pace of modern life.

The Position of Czech and Slovak Art in the International Art World, by Jaroslav Jira

The young Prague art historians have therefore taken the first step toward the rediscovery of previously forbidden paintings, and the great interest exhibited in the aforementioned Prague exhibition shows clear-ly that the Czech public is truly interested in "paintings which spring from the depth of imagination". This reflects that deeply rooted brooding and philosophizing spirit of the Czech people.

Carnegie Show, October 20th, 1930

An article reporting on the 29th Carnegie Institute International Exhibition of Modern Painting having taken place in Pittsburgh in the Fall of 1930. Uprka and other prominent members of SVUM were featured.

"Artists, art critics and ordinary people were going over the hills to Pittsburgh this week to the 29th Carnegie Institute International Exhibition of Modern Painting. There was plenty to see. The Pittsburgh show has become the most important annual exhibition of modern art in the U. S. Stretching on through gallery after gallery are 439 paintings representing the work of most of the well known modern painters in the world today. Over 1,000 U. S. paintings were submitted, 152 were hung. In all, 137 European and 99 U. S. artists were represented. The two heroes of the Pittsburgh show were French. Neither was present at the Founders Day opening: Henri Matisse and Pablo Ruiz Picasso."

The Mucha Connection

Mucha recalled "He came and sat at our table, between [Władysław] Ślewiński and me. He was a powerfully built Breton, dressed in something that looked like a national costume. On his head he wore an astrakhan cap and across his shoulders a wide cloak with ornamental clasps. Madame Charlotte introduced him as a sailor who was also a painter: Monsieur Gauguin. We soon became friendly [...]. From now on, Gauguin came every day".

Alphonse Mucha, Memoirs No. 94, 95, 364, 373, 372.3, & 1196

Jožka welcomed us and took us straight into the garden where we lay under the fruit trees. After a moment the local museum band appeared behind the bushes to welcome us. Drinks were passed around. I can see the whole scene which moved us all by its beauty. Girls in colourful headscarves and white sleeves completed the impression and people held their breath so as not to spoil the moment. Rodin, moved to tears by the unspoilt beauty of it all, shook my hand and admitted he never experienced anything like it and would love to stay forever. (No. 372.3)